APPLICATION OF DOUBLE-LOOP LEARNING WITH LEADERS IN HIGHER EDUCATION

MURPHY, JEANIE

THE SCHOLASTIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE (SRI) MICHAEL-CHADWELL, SHARON

CAPELLA UNIVERSITY

Dr. Jeanie Murphy

Founder, J. Murphy & Associates and Assistant Vice President

The Scholastic Research Institute (SRI).

Dr. Sharon Michael-Chadwell Capella University.

Application of Double-Loop Learning With Leaders in Higher Education

Synopsis:

The current qualitative research study examines the decision-making process of leaders in higher education to identify difficulties of measuring the quality of decision making, examines perceptions of higher education leaders on how poor decision making arises and how poor decision making might be remedied.

APPLICATION OF DOUBLE-LOOP LEARNING WITH LEADERS IN HIGHER EDUCATION

by

Jeanie Murphy, DBA, Founder, J. Murphy & Associates and Assistant Vice President, The Scholastic Research Institute (SRI)

Sharon Michael-Chadwell, Founder and President, Keen Notes Consultancy and Assistant Professor at Capella University

Abstract

To improve decision making, engagement is a critical component that promotes organizational learning; ineffective decision-making processes continue to result in challenges, increased time and costs, and stressors for the most stakeholders. The current qualitative research study examines the perceptions of leaders in higher education regarding the decision-making processes, the measures used to qualify quality decision making, and solutions to approach ineffective decision-making processes. The research also assesses behaviors and practices of leaders in higher education institutions to determine if organizational learning, preferably double-loop learning, occurs during the decision-making process. Improvements in the decision-making process may be a derivative of constructive feedback, self-reflection, and engagements, which furthermore stimulate organizational learning. Findings showed that the acceptance and application of the double-loop learning concept will require a change in the behaviors, protocols, and measures associated with the decision-making process deployed within higher education systems.

Key words: Decision making, higher education, leadership, organizational learning, double-loop learning

Introduction

Competition, limited resources, increased diversity, and generational changes in the workplace are requiring leaders to reexamine current leadership practices and question whether the workplace is conducive to improved learning and productivity. Within institutions of higher learning, apparent challenges for education leaders include student and faculty retention, technological advancements, and the influence of federal- and state level-policies (American Association of State Colleges and Universities [AASCU]; 2014); Economist Intelligence Unit [EIU]; 2008). Thomas (2014) noted, the right first time agenda has been advanced as a solution to organizational problems. To improve decision making, Thomas asserted engagement is a critical component, which promotes organizational learning.

Argyris and Schön (1974, 1978) asserted organizational stakeholders who do not question goals, values, plans, and rules are maintaining a state of operationalization or single-loop learning rather than double-loop learning in which organizational members are critically scrutinizing the status quo. In the field of higher education, discussions related to student retention have begun to promote political and scholastic discussions concerning various practices that are impeding the success of students and acquiring professors (Harnisch, 2012; Nelson- Porter, 2013). The purpose of this paper is to present the difference between Argyris and Schön’s concept of single- versus double-loop learning and share how the concepts have been applied to the decision-making processes performed by leaders in higher education systems who are tasked with improving student and faculty learning and outcomes.

Background of the Problem

As institutions of higher learning continue to operate in an environment whereby leaders must face the issues related to a demographic change that influences enrollment and instructional practices, opportunities are present to assess how to address what appears to be a disruption in the system especially when considering the effects on funding and the budget (Wilcox & Ebbs, 1992; Zumeta, 2009; 2012). Leaders governing institutions of higher education continue to face concerns related to quality assurance and governance, while trying to remain autonomous (Dill, 2007; Stowell, 2004). On one hand, the need is to examine policies that exist to widen access and participation for a more diverse group learners and continuing the need of maintaining academic standards. In contrast, Sowell (2004) concluded a need exists to question assumptions regarding the role of higher education and the systems constituting its existence and significance.

When the practice is to not question goals, values, plans, and rules, Argyris and Schön (1978, 1974) defined this type of culture as resulting from single-loop learning versus one in which variables and factors are subjected to critical scrutiny or a double-loop learning framework. Examining the problem within the context of single- versus double-loop learning prompts an awareness that higher education leaders are maintaining an environment in which the question, Are the right things happening? has not transforms to Are collective supported efforts happening for the right reasons? (Yeo, 2007). Ineffective decision making results in “more appeals and challenges, increased costs and time, and stress for the individuals involved. Over recent years, the ‘right first time’ agenda has been advanced as a solution to this problem” (Thomas, 2014). To improve the experiences of faculty members and learners, higher educational leaders must reexamine how to improve administrative efficiencies while looking to gain competitive advantage over rivals (Dunnion & O’Dovovan, 2012).

The current qualitative research study examines how double-loop learning applied during the decision-making process could assist leaders in higher education with the decision-making protocols, measures used to qualify quality decision making, and solutions to approach ineffective decision-making processes. To improve decision making, engagement is a critical component, which can promote organizational learning; ineffective decision-making processes continue to result in challenges, appeals, increased time and costs, and stressors for the most stakeholders (Thomas, 2014). The current research also examines behaviors of leaders in higher education institutions to assess organizational learning, preferably if double-loop learning is present during the process. The following research question guided the development of the study: When applying double- versus single-loop learning, how have decision-making processes and protocols, aimed to approach challenges faced in higher education institutions, improved the behaviors and culture of the institution and retention of faculty and learners?

Literature Review: Challenges Impacting Higher Education

Issues and trends in higher education arena continue to be published by organizations such as Hanover Research [HR] (2013), the Alumni Association Network (AAN), New Media Consortium [NMC] (2013), and AASCU (2014) derived from customize research on challenges impacting high educational systems. The trends of interest in higher education include and are not limited to the number and types of program offerings, the cost of the program offerings, and platform (HR, 2013). The 2013 Hanover Report furthermore revealed interests for research for higher education institutions are on data concerning the impact of institutions, strategies and strategic planning. Other areas of interests for customized research, which resulted in higher education institutions collaborating with independent consulting groups, are data on funding solutions resulting from award-winning multimillion dollar grant writing, innovations for improving institutional brand awareness and perceptions, and training program offered within institutions (HR, 2013).

Dr. Brenda Nelson-Porter (personal communication, March 14, 2015), the CEO and Founder of Brigette’s Technology Consulting and Research Firm established the Alumni Association Network, known as AAN, in 2007 and has discovered from a virtual network of scholars interesting revelations regarding the world of higher education, specifically academics. As the virtual network is aimed to increase awareness about academic issues occurring in higher educational institutions from research, social media platforms, and conversations; interestingly, personal experiences from scholars across the country provide unique perspectives on challenges faced in higher education.

Challenges identified within higher education in which graduate students face include the lack of knowledge about research and the importance of research and limited publishing and research opportunities upon graduation, especially for online graduates (Nelson-Porter, 2012; Nelson-Porter & Grey, 2009). Issues within higher education affecting stakeholders might consist of curriculums, which may not mimic the current changing workforce.

Additionally, there may be unethical grading practices (e.g., assigning an Incomplete grade when not warranted, failure to deduct points on writing assignments when writing standards are not followed, failure to assigning adjunct professors classes for refusing to increase low grades of prior learners), and retention of learners, acquiring professors, and members of the academic affairs. Retention involves focusing on nonmilitary learners who are not eligible for the GI Bill, acquiring professors who desire to follow writing and research standards, and members of the academic affairs division who are serving as human mediators between the policies and complaints (Harnisch, 2012). The global network of scholars aims to change existing practices and protocols associated with decision-making processes influencing higher education industries, while ensuring learners and graduates receive quality care and opportunities, of which have been affected by hidden societies aimed to deter a certain scholar population from effectively reaching their full potential to make a presence in the global societies, especially in the academic and research sectors, to include the legal, technical, and natural healthcare arenas.

Findings in the 2013 Horizon Report confirmed the aforementioned challenges affect faculty training, processes, assignments, and practices in regard to determining which teaching or learning platforms becomes available, the modalities of learning environments in which instructions are practiced, and personalization of learning environments supported by emerging technologies (NMC, 2013). The report presented six themes:

1. Training for faculty requires a mastery of digital technology.

2. An increase of technology for research and scholarship outperform existing assessment measures.

3. Existing processes limit the advancement of technology in the education arena.

4. The necessity for adaptive learning technology is unsupported by current technology or teaching and or practices.

5. Many academicians fail to demonstrate competency of new technologies in facilitation and assessment of learning or in the positioning of personal explorations.

6. The traditional model of higher education continues to diminish confirmable by the amount of competitors in the market.

A review of literature furthermore revealed significant challenges for higher education directly associated with technology. Technology is a driving force, which supports innovation and globalization, and often considered as a disruptive innovation (EIU, 2008) which can improve and or impede processes. Considering processes, higher education leaders determine how, when, and at what rate technology should be implemented into existing processes, implemented into teaching practices, and learning platforms. Based on survey findings derived by the representatives of EIU (2008), higher education professionals and corporate professionals agree, technology, and advancing technology are critical factors for corporate and academic partnerships. Corporate leaders have the expectation of academic institutions using and teaching on cutting edged technological platforms; academic institutions require technology to provide new teaching and learning platforms. The relationship could be reciprocal although there can be unforeseen challenges, such as operational challenges from both entities preventing reciprocity (EIU, 2008).

Higher education and its accountability continues to be a priority for lawmakers, who make federal and state statutes on the governance of higher educational institutions (AASCU, 2014). At the federal level, legislation controls eligibility for funding for various institutions and grants. The reactivation of the Higher Education Act (HEA) of 1965 was a strategy to increase access to higher education institutions and lower costs of tuition directly, impacts decisions derived by leaders and the process used to determine how leaders of educational institutions will adhere to the legislation (AASCU, 2014).

At the state level, higher education policies affect the decision-making processes of how agendas are settled when determining governance and funding (AASCU, 2014). The politics at the state levels often consider precedents from other states. The rulings affect enforcement of policies and influence how future policies proposals are created and contributors to State Relations and Policy Analysis Teams presented several issues at the state level. The issues were harnessing higher education to address state economic goals, (b) agreements linking state funding and tuition policy, (c) allocation of state higher education appropriations, (d) state educational attainment and college completion goals, (e) vocational and technical education, (f) college readiness; (e) STEM related initiatives, (g) state capital outlay and deferred maintenance funding, (h) guns on campus, and (i) immigration (AACSU, 2014). Nelson-Porter (2009) suggested by promoting independent dissertation consultants (IDCs), graduate students may make better decisions on appropriate research topics and research methods that reflect current issues, trends, and happenings in the private and public sectors, which may lead an increase retention in higher educational systems and to a quality workforce.

Framework: Single- Versus Double-Loop Learning

In understanding the behaviors adopted by the workforce, researchers have categorized differences in behaviors by various theories to show how solutions emerge to combat challenges. The espoused theory posits managers believe that collaborative acts solve problems within a work unit; the theory-in-use, on the other hand, posits that the managers’ beliefs are based on their mental model in that authoritative behaviors derive the decision-making processes and performances (Argyris & Schön, 1978, 1974; Fraser, 2015). The mental maps individuals develop are situational, which may involve planning, implementing, and reviewing actions (Argyris & Schön, 1974). Unfortunately, Argyris and Schön asserted most individuals do not understand the constructs of their mental maps and why certain behaviors emerge in various situations.

Factors governing behaviors could be contingent on three dimensions: governing variables, action strategies, and consequences (Argyris & Schön, 1974). Governing variables are the behaviors that modulate actions of individuals. Action strategies are the constrained actions displayed by individuals. Collaboratively, the governing variables and action strategies can result in expected or unexpected compatible/conflicting consequences whereby the latter could be observed within the context of single- and double-loop learning (Argyris & Schön, 1974).

Single-loop learning occurs as a result of changes in behaviors or actions derive from unexpected results from original goals or new tactics, which are based on experiences; whereas, double-loop learning occurs as a result questioning and applying the decisions that resulted from incorporating the three dimensions or better yet, examining alternative solutions and their appropriateness to the desired outcome (see Figure 1) (AFS, 015; Argyris & Schön, 1974; Greenwood, 1998).

Double-loop learning from an organizational learning perspective involves the single- loop process of effective and efficient solution identification followed by deep analysis for continuous process improvement in the decision-making process (Kelly & Lauderdale, 1999). Researchers postulated examples of challenges with the double-loop learning process such as with decisions made by lawmakers and leaders in academic institutions by which decisions are not transparent, based on bias, and or discretionary influence is evident in political arenas of business (Kelly & Lauderdale, 1999). One of the major challenges is the adoption and learning organizational leaders experience to become increasingly aware of critical factors identifiable with traits of an organization in which learning occurs (Kelly & Lauderdale, 1999).

A learning culture reflects the concept of single-loop or double-loop learning. The existence of three cultures has been found to be entrenched in all organizations (Schein, 1996):

1. Operator culture: An internal culture derived based on its operational success.

2. Engineering culture: Designers and technocrats driving core technologies.

3. Executive culture: Executive management team to include the CEO and junior executives.

Schein (1996) concluded a misalignment could emerge amongst subcultures and the outcome can compromise the success of organizational learning.

The learning environment reflects on organizational values and norms as well as aligns with espoused behaviors that possibly helps render a more meaningful experience (Greenwood, 1998). Within the context of systems thinking, one of the basic tenets of the framework is applicable: “parts and wholes snapshots rethought with processes of learning and coevolving over time” (Ing, 2013, p. 528). Validating the espoused theory, structures or members within systems interact to produce results, outcome, and effects, reaffirming the interconnectedness of behaviors of members or processes and components of systems that influence outcomes.

Validating that behaviors influence the culture of higher education institutions, the current research study aims to show the distinction between outcomes of single- versus those of a double-loop learning environment. Double-loop learning supports the raising of questions and pursuing solutions designed to improve single-loop learning solutions (Freeman & Knight, 2011). Single-loop learning plays a role in cultural development when stakeholders simply follow directions, and double-loop learning plays a role in cultural progress when all major stakeholders acquire the ability to assess issues and solutions and form opinions, questions, and measures to approach these issues faced by leaders in higher education institutions. The application of knowledge based on the exploration of new learning opportunities is more prevalent within a double-loop learning environment (AFS, 2015; Freeman & Knight, 2011).

Descriptive Analysis and Emergent Themes

For the current qualitative research study, data was collected from 21 higher education leaders using SurveyMonkey with the assistance of Brigette’s Technology Consulting and Research Firm. Over the course of 2 weeks, leaders from various academic institutions were invited to participate. The primary means of solicitation for participation was a purposive sampling using electronic communications such as e-mails and instant messaging to potential candidates through social media platforms. The solicitation was also a combination of snowballing as participants, who were solicited, were asked to refer a colleague. In addition to demographic questions, the following questions were part of the data collection protocol, which reflect key terms (assessment, measures) derived from the concept of double-loop learning offered by Freeman & Knight (2011):

1. What are the human challenges impacting your decisions in your current role?

2. What are the technical challenges impacting your decisions in your current role?3. Do you solicit feedback from others on your decisions? Why?

4. When obtaining feedback from individuals who are impacted by your decision- making process, do you and your management team self-reflect on the decision- making? Explain.

5. What protocols are made to improve your decision-making processes?

6. How do you evaluate any changes made to the original decision-making processes after implementing changes based on the effects or outcome of your decisions?

7. What recommendations would you offer to higher education stakeholders to strengthen the assessment of decision outcomes?

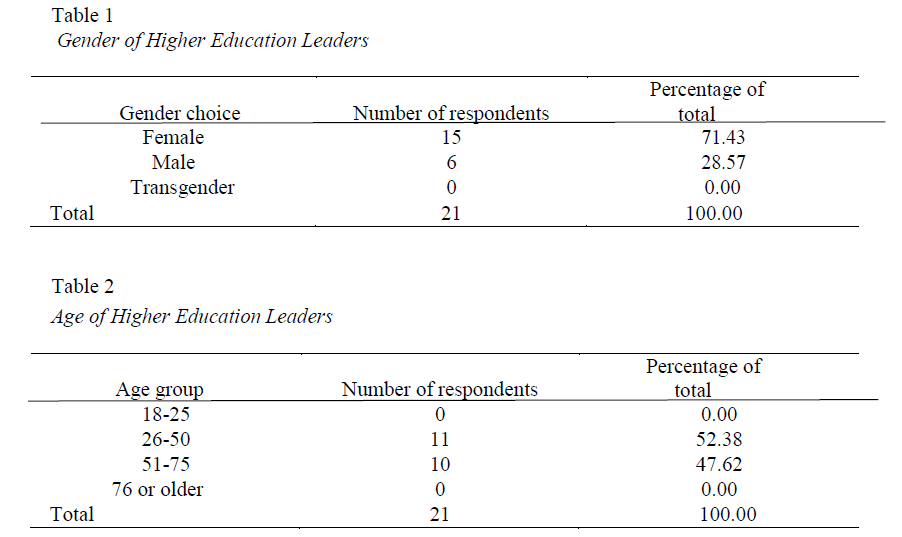

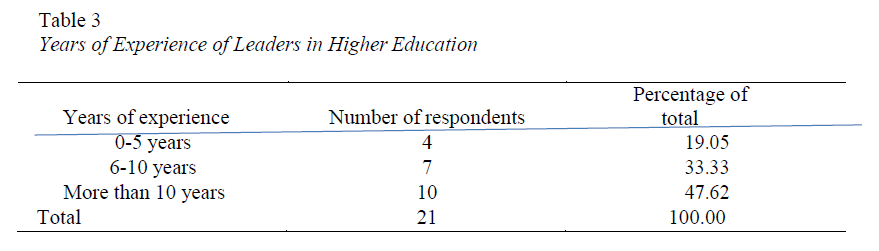

The participants were aware of their rights in relation to participating in the study, knowing participation was voluntary. Of the 21 leaders, three only responded to the demographic questions, while 18 responded to the majority of the questions. Tables 1 through 3 show the demographic data of the higher education leaders (HELs) who completed the questionnaire. Although there is no way of verifying who responded, the analysis was conducted based on the information provided through SurveyMonkey.

As shown in Table 1, more female leaders participated in the research study. Tables 2 and 3 show that the age of these leaders in higher education ranges from 26-75, and most had 10 or more years of experience. Results may suggest that women may be more open to sharing information about challenges faced in higher education institutions or leaders age 26 or higher have ample amount of experience to discuss the most sufficient issues impacting the operation of academic institution and progression of academic stakeholders.

Human Challenges Impacting Decisions Made in Higher Education Systems

Nineteen leaders (referred to as HEL) provided diverse responses on human challenges impacting their decisions; these challenges derive from the management team, co-workers, juniors, students, and external constituents. The human challenges of the management team, which consists of administrators or HELs, was reported as making poor decisions as well as requesting immediate actions, which influence other leaders’ ability to accomplish goals. HEL7 stated, “Relying on others to provide prompt and accurate responses and feedback relative to processes and procedures that are not clearly defined is a significant human challenge. Learning how to best deal with the various management and personal styles of communication amongst those you constantly work with is another challenge.” HEL2 and HEL5 alluded leaders do not understand the nature of the problem to satisfactorily derive a solution because a distance exist between the stakeholders.

Because of massive internal changes and the absence of understanding the level of authority leaders have to make decisions, motivation becomes an issue. In addition to the administration, a lack of student preparation and training exists for the ‘juniors.’ HEL6 stated, the “amount of time I need to spend with my students and understanding their learning outcome” is a human challenge. Thus, balancing tasks and life becomes a challenge. HEL3 and HEL10 added the changes in the competitive markets and adapting to a rapidly changing worker profile and skills requirements and cultural barriers and language influence the decisions. When a lack of quality human resources and retention of faculty exists to approach these challenges, a certain level of professionalism and customer care may deteriorate.

Technical Challenges Impacting Decisions in Higher Education Systems

Three of 18 leaders, who responded to this question, did not identify any technical challenges that influenced decisions in higher education. Identifying the overuse of technology and the management of data as challenges were surprising. Twelve of the leaders implied that limited access to technical resources was a primary challenge in the decision-making process.

Several educational leaders expressed difficulties in keeping abreast of current, changing, and evolving technologies, to include the evolution and access to software:

1. HEL14 stated, “using new technologies appropriately and fully understanding their benefits” are technical challenges which impact decisions revolving around academic performances.”

2. HEL9 shared, “Technical challenges include not having access to software or resources that may be used in various facets of higher learning. Hence, it is challenging to branch out and use other technical aspects if the content will not be supported or utilized due to access.”

3. HEL6 expressed, “Software for everyday functions seems to be unavailable frequently due to technical issues and/or computers are just plain slow. Not being able to have administrative rights on my workstation. Having to rely on work orders being submitted and then waiting on response, often days or sometimes more than a week.”

Although specific software packages or Internet browsers were not mentioned, the implication from the responses of the higher education leaders suggests a certain level of

frustration to complete daily tasks. Remote capabilities, Internet access, and communication using computers are essential components of the decision-making processes. Proper funding, however, as hinted by HEL4, may be a primary reason institution investors are not able to fund technological changes associated with software advancements and points of access.

Solicitation of Feedback About Decisions

Two of the 18 leaders do not solicit feedback about the decisions made related to academic affairs. Fifteen leaders indicated solicitation of feedback is a form of best practices to gain buy-in from others, (b) broaden their knowledge base, (c) make right decisions, and (d) gain sound results. Respective to the solicitation of feedback, team participation emerges as a theme as new perspectives and ideas to include interaction from administrators, different experiences are present. HEL6 explained:

Often reports and other important documents require input from the members of my team. I rely on them to provide timely and accurate feedback. Whenever decisions affect others, I reach out to them to get their input to help them understand the process and gain knowledge related to the situation.

As situations vary, the need for feedback to enhance or complement the knowledge of leaders is necessary. HEL15 ensures other perspectives are considered before making final decisions. HEL13 also proclaimed feedback as a means of monitoring decision making to ensure directions are correct.

Self-Reflection of Decision-Making Processes

Fifteen leaders self-reflected following the making of a decision. The purpose of self- reflection used during the decision-making process has been to enhance collective collaboration and transparency, save time and money in the future, empower impacted individuals, gain understanding about the ramifications of final decisions, and learning from

lessons. HEL5 stated self-reflection voids “re-creating the wheel.” HEL13 related self-reflection to monitoring whereby both strategies aim to prevent long periods of wrong direction; however, ensures knowledge from experience. HEL3 used the plus/delta method of reflecting for continuous improvement. Two of the 15 leaders implied the process is limited and might be practiced more to obtain better decision-making results.

While self-reflection can commence prior to or following the decision making, the process can take place in the form of team participation, similar to obtaining group feedback. HEL9 implied self-reflection prior to decision making increases confidence about the decisions as decisions are made based on the level of impact. HEL9 shared, “The team will more so re-cap (if needed) to see if we need to follow up on anything and discuss the delivery of the message.”

Although HEL16 stated management does not engage in the process, HEL18 shared through team participation, important decisions are discussed extensively. HEL2 asked for “feedback from all stakeholders to facilitate improvement on the learning community.” HEL12 stated that different perspectives often complete a picture. Regular team meetings or group meetings, whereby self-reflection commences according to HEL6, helps each member with understanding the implications and how to work on improvements for the future.

Protocols to Improve Decision-Making Processes

Five leaders did not state if a protocol was used to improve their decision-making process. Formal protocols mentioned include using the plus/delta method, referring to company policies, engaging in interactive sessions, and adopting varies strategies. HEL3 uses 80, the decision-making matrix, and key metrics whereby predictions based on the metrics are used to help change undesired outcomes. HEL5 stated many written processes and procedures ensure the decision-making process is clear and straightforward. When no processes and

procedures are present, then the decision making becomes more difficult. Thus, personal ethics, as indicated by HEL11, could be an alternate.

In addition to listening to advice like HEL15’s, other educational leaders gather feedback and pertinent information prior to making a decision from internal stakeholders and experts, such as senior colleagues, as well as external stakeholders and experts. HEL13, however, believes assessments or evaluations are applicable to gain knowledge about situations. HEL8 stated, evaluating prior decisions and how individuals respond, helps with considering future decisions and effective ways to communicate and execute during the decision-making process.

Engaging in interaction sessions also helps stimulate creativity. HEL4 looks for creative solutions to approach problems and strategies to stimulate productivity, quality, and accountability. HEL12 identifies problems or opportunities, alternative solutions, pros and cons for proposed solutions, and makes decisions based on the weight of the pros and cons.

Evaluation of Changes Implemented to Original Decision-Making Processes

When evaluating the changes implemented to the original decision-making processes, 2 of the 18 leaders were unsure how the question was applicable. Nine leaders implied the evaluation of data obtained by self-reflection and from feedback of peers and other stakeholders, are used to track decisions, note ramifications, assess student outcomes, check expected results, and monitor desired outcomes. Critical feedback, survey results, comparative analysis, and observation help with evaluating how the process might differ in the future based on factors emerged during the processes. HEL13 noted, “The evaluation process is conducted using the proper tools, statistical analysis, exception reports, Pareto charts, and status reports.” HEL2 explained, “As changes are implemented, we constantly assess and make changes as needed from data gathered.” However, HEL4 stated, “Changing the equation is windbreak throw[ing] a curse.” Because change leads to movement, HEL14 asked what directions did decisions involve relationships, and what behavioral changes emerged? HEL1 asked, was there compliance with the decision? HEL9 concluded, answering, “Some decisions, however, are made due to a process or policy in place which you cannot change.” Thus, when policies restrict changes, noting how deductive and inductive reasoning plays a role in decision making as HEL5 contends may be an effective change agent that senior leaders can can use to reflect on to override current policies.

Recommendations by HELs to Higher Education Stakeholders

As potential change agents, the 18 HELs provided recommendations to higher education stakeholders to strengthen the assessment of decision outcomes. HEL2 believes decisions need to be approached and altered at the learner level, based upon needs of the community. Four leaders concluded that identifying measurable outcomes, such as student outcomes, and understanding the intended outcome of the decision are appropriate assessments of decision outcomes. Outcomes have derived from careful on-hands study and not secondary or tertiary data, common assessments, and evaluations of the resulting data. HEL13 stated, “The planning, implementation, monitoring, and correction, if needed, is always the best assessment direction.”

Three leaders focused on the thinking process. HEL15 stated that stakeholders should “consider implications of decisions before implementing them and monitor responses to determine if changes need to be made.” HEL5 recommends critical thinking as a means to think smarter. HEL4 asks, “How can we think about Prada problems to have solutions that make a huge difference?” The process of interactions with peers and team members enables stakeholders to self-reflect, seek advice, become knowledgeable of resources, be receptive to others’ knowledge, inspire collaboration among stakeholders, engage more stakeholders vertically and horizontally, and allow the decision makers to have more of a voice in decisions which directly impact them or their staff versus executing decisions which have already been made. The recommendations suggested by HEL6 include meeting regularly, as well as ensuring and adhering to open communication absent of pressure. Communication with senior leaders and other stakeholders should involve respect and honoring opinions and feedback without getting defensive or personalizing the activity.

Although HEL14 believes awareness and understanding are important for all stakeholders involved in the processes, “some things should remain confidential.” For example, resources and staffing should be clearly understood by all. The process should be conducted in an efficient manner to avoid disclosing pertinent information. HEL10, however, believes stakeholders should not seek followers who will agree with everything. “This could hurt the organization and set it up for failure.”

Implication of Double-Loop Learning and Future Research Suggestions

Future researchers should consider exploring leadership styles, to include visionary mentorship, that are effective for implementing and deploying double-loop learning. Not implementing actions offered by Freeman and Knight (2011) could maintain an organizational learning disability (Gorman, 2004), thereby sustaining a single-loop learning culture. Based on the findings from the current study, the application of double-loop learning could occur if higher education leaders implement the following recommendations:

1. Reexamine current leadership practices and question if the workplace is conducive to improved learning and productivity;

2. Examine consequences of decisions from a wider perspective;

3. Question goals, values, plans, and rules and carefully scrutinize the status quo; and

4. Re-evaluate and reframe goals, values, and beliefs supporting complex thinking and engagement.

Visionary mentoring, coined by Dr. Brenda Nelson-Porter in 2008, involves establishing close rapport with mentoring protégés to ensure protégés have appropriate research and accurate data and utilize adequate methods, instruments, and technologies to conduct quality research, which can be applied to qualifying the foundation of decision-making processes and accurate reporting. Visionary mentoring can foster environments supportive of organizational learning as a platform to transform organizational cultures grounded on continuous improvement and supported through research (Nelson-Porter, 2008; Sellnow, Veil, & Anthony, 2015). To approach ego issues, visionary mentors can assist with helping protégés promote inclusiveness of multiple viewpoints and respect for others’ perspectives to reduce any negative social impacts during the decision-making processes.

Secondly, researchers may apply the multi-loop social learning theory to organizational cultures respective to how organizational policies and procedures influence decision-making process, as higher education systems comprised of complex business models are aimed to emerge global research initiatives (Blackmore, 2007; Medema, Wals, & Adamowski, 2014). During the revaluation phrase, visionary mentors can conduct perception management research to ensure the findings of quality and ethical research is applied to appropriate human resources’ policies and procedures aimed to fit into the scheme of global learning and stimulating social change, internal and external of higher education institutions (Blackmore, 2007). Perception management is a communication strategy, which includes gaining a competitive advantage by facilitating what is known as information warfare (Koop, 2005). In addition, the process includes multiple strategies for behaviors intended to provide purposeful deceit. Deception can be exhibited in four ways: (a) degradation, destruction, or denial of information; (b) corruption or deception; (c) denial or disruption; and (d) denial (Koop, 2005). Here, visionary mentors, who engage in netweaving, might be tasked with assessing any massive internal changes stimulated by global academic- related research initiatives, to include the participation of acquiring professors, to ensure seasoned and new emergent scholars do not become a victim of information warfare.

Conclusion

The focus of organizational learning should not be focused primarily on the operator and executive cultures (Schein, 1996). The executive adapting learning processes to meet the challenges of the 21st century should consider adopting all cultural dimensions to include the engineering culture (Schein, 1996). This same conclusions applied to the higher education community will prompt double-loop learning. Within the context of double-loop learning, leaders and juniors, who examine behaviors that either help support the adherence to the same outcome or alternative solutions and their appropriateness to the desired outcome, will derive quality decisions to approach human and technical challenges effectively. Based on the current study’s finding, one could infer that the HELs’ support a double-looped learning environment concerning the (a) solicitation of feedback about decisions, (b) self-reflection of decision- making processes, (c) evaluation of changes implemented to original decision-making processes, and (d) protocols used to help improve decision-making processes. Part of this willingness is that the HELs are attuned to the human and technical challenges and their effects on decision making faced within their organization.

The overall behavior of an organization is characterized based on the theory-in-use behavior rather than the espoused theory, when organizational members construct

image of events and solutions creating a risk of developing an incomplete picture of the situations and their role in approaching the situation (Argyris & Schön, 1978). Organizational learning helps with understanding the mental models and how models can influence the culture of an organization. To transition from a single- to double-loop learning environment, academic organizational leaders must be willing to detect and correct internal and external variables that could hinder learning whereby the knowledge and innovations gained from clear assessments of faculty and student outcomes become a part of the organization’s memory (Argyris & Schön, 1978).

Thus, for their institutions to be competitive, higher education leaders might consider challenging old and unethical paradigms and consider their appropriateness in meeting the challenges facing academic paradigms and their stakeholders, by initially contracting and acquiring professors who will be mentored for the role of full-time/tenured professor. Feedback from acquiring professors could assist in devising more appropriate applied assessments, whereby the findings may derive solutions geared to improved retention and the deployment of new technologies. To remain competitive, higher education leaders must further engage in visionary mentorship or deploy visionary mentorship whereby learning continues to evolve through a validation processes that involve applying case studies and industry-related research to the findings that emerged from internal evaluations and assessments.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

References

AASCU (American Association of State Colleges and Universities). (2014, January). Top 10 higher education state policy issues for 2014. Policy Matters, 1-5. Retrieved from http://www.aascu.org/policy/publications/policy- matters/Top10StatePolicyIssues2014.pdf

AFS. (2015). Single-loop and double-loop learning model. Retrieved from http://www.afs.org/blog/icl/?p=2653

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective, Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Blackmore, C. (2007). What kinds of knowledge, knowing, and learning are required for addressing resource dilemmas? A theoretical overview. Environmental Science & Policy, 10(6), 512-525.

Dunnion, J., & O’Donovan, B. (2014). Systems thinking and higher education: The Vanguard model. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 27(1), 23-37.

Dill, D. D. (2007). Quality assurance in higher education: Practices and issues. The 3rd International Encyclopedia of Education, 1-13. Retrieved from http://www.unc.edu/ppaq/docs/Encyclopedia_Final.pdf

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). (2008). The future of higher education: How technology will shape learning. Retrieved from http://www.nmc.org/pdf/Future-of-Higher-Ed-(NMC).pdf

Fraser, D. (2015). What is the difference between espoused theories and theories in use? Retrieved from http://www.drdavidfraser.com/2015/03/20/whats-the-difference-between- espoused-theories-and-theories-in-use/

Freeman, I., & Knight, P. (2011). Double-loop learning and the global business student. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 41(3), 102-127.

Gorman, L.L. (2004). Leadership and organizational cultural values that influence organizational learning: Fostering double-loop learning. (University of Phoenix: Dissertation, 2004).

Greenwood, J. (1998). The role of reflection in single and double-loop learning. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27, 1048-1053.

Hanover Research. (2013). A look at how higher education institutions used research across 2013 to make high-impact decisions. Higher Education Market Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.hanoverresearch.com/media/Hanover-Research-Higher-Education- Year-in-Review-2013.pdf

Harnisch, T. L. (2012). Changing dynamics in state oversight of for-profit colleges. American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Retrieved from http://www.aascu.org/

Ing, D. (2013). Rethinking systems thinking: Learning and coevolving with the world. Systems Research & Behavioral Science, 30, 527-547.

Kelly, M. J., & Lauderdale, M. L. (1999). Mentoring and organizational learning. Professional Development-Philadelphia, 2(3), 19-28. Retrieved from http://www.utexas.edu/research/cswr/survey/journal/articles/020304.pdf

Kopp, C. (2005). Classical deception techniques and perception management vs. the four strategies of information warfare. Retrieved from http://www.csse.monash.edu.au/publications/2005/IWAR05-Kopp.pdf

Medema, W., Wals, A., & Adamowski, J. (2014). Multi-loop social learning for sustainable land and water governance: Towards a research agenda on the potential of virtual learning platforms. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 69, 23-38. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2014.03.003

Nelson-Porter, B. L. (2013). Acquiring professor. Alumni Association Network. Retrieved from http://www.alumniassociationnetwork.org/GlossaryAcquiringProfessor.html

Nelson-Porter. B. L. (Producer). (2012, May). The importance of research [Video podcast]. USA. Available at http://vimeo.com/42168455

Nelson-Porter, B. L. (2009). Higher education can decrease overhead by promoting independent dissertation consultation. Retrieved from http://www.brigettes.com/Training/DissertationConsultant.htm

Nelson-Porter, B. L., & Grey, C. (Ed). (2009, December). Submission of scholarly articles. Retrieved from http://www.alumniassociationnetwork.org/pdfs/ ScholarlyJournalReport2009December.pdf

New Media Consortium (NMC). (2013) Horizon Report: 2013 Higher Education Edition. Retrieved from http://www.nmc.org/pdf/2013-horizon-report-HE.pdf

Schein, E. H. (1996, Fall). Three cultures of management; The key to organizational learning. MIT Sloan Management Review. Retrieved from http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/three- cultures-of-management-the-key-to-organizational-learning/

Sellnow, T. L., Veil, S. R., & Anthony, K. (2015). Experiencing the reputational synergy of success and failure through organizational learning. The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Reputation, 235-248.

Stowell, M. (2004). Equity, justice and standards: Assessment decision making in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(4), 495-510. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download? doi=10.1.1.494.6210&rep=rep1&type=p

Thomas, R. (2014). Administrative justice, better decisions, and organisational learning. Public Law, 215, 1-23. Retrieved from shttp://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/ papers.cfm?abstract_id=2477969

Wilcox, J., & Ebbs, S. (1992). The leadership compass. Values and ethics in higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ericdigests.org/1992-1/compass.htm

Yeo, R. K. (2007). (Re)viewing problem-based learning: An exploratory study on the perceptions of its applicability to the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, (22, 4), 369-391.

Zumeta, W. (2012). States and higher education: On their own in a stagnant economy. The NEA Almanac of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/_2012_Zumeta_18Jan12.pdf

Zumeta, W. (2009). State support of higher education: The roller coaster plunges downward yet again. The NEA Almanac of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/HE/HE_NEA_Resources1_al09p29.pdf

Authors’ Biographies

Jeanie Murphy has over a decade of experience in higher education and over a decade of experience in operations management. She has presented at various conferences on the topics of leadership, mentoring the adult learner, and entrepreneurship. Jeanie is the chief executive officer and founder of the consultant company, J. Murphy & Associates, and is the Assistant Vice President of the Scholastic Research Institute (SRI) operated under the umbrella of the Alumni Association Network (AAN).

Sharon Michael-Chadwell has more than 20 years of experience in higher education in the United States, 18 years in public education, and 13 years as a corporate manager. She has publications in the areas of gifted and talented issues and marketing issues related to higher education. She is an assistant professor with Capella University as well as chief executive officer and founder of Keen Notes Education Consultancy.